Australian Asthma Handbook

The National Guidelines for Health Professionals

Cite

Before starting treatment

Table

| Situation | Total dose per occasion | Administration |

| Cough or wheeze without visibly increased work of breathing |

2–4 actuations x salbutamol 100 microg/actuation If symptoms do not resolve within a few minutes, give 2–4 more actuations. |

With spacer: Add 1 actuation to spacer – child takes 4 breaths in and out of spacer. Immediately repeat for second and subsequent actuations until the recommended number of actuations have been given. |

| Symptoms with increased work of breathing |

12 actuations x salbutamol 100 microg/actuation If symptoms do not resolve within a few minutes, give 12 more actuations and call 000 for an ambulance. If symptoms still do not resolve, or recur within 3 hours, parents/carer should take child to ED or call 000 for an ambulance. |

Table

| Severity of Exacerbations | Pattern of exacerbations and symptoms | ||

| Exacerbations less than once every 3 months, and no symptoms between exacerbations | Exacerbations more frequent than once every 3 months, and no symptoms or infrequent symptoms between exacerbations | Symptoms between exacerbations (any of):

| |

Mild Exacerbations quickly resolve with salbutamol | Not indicated | Consider | Indicated |

Moderate–severe ≥1 exacerbation in past year required ED or oral corticosteroids | Consider | Indicated | Indicated |

Life-threatening ≥1 exacerbation required hospitalisation or PICU | Indicated | Indicated | Indicated |

Additional information

ED: emergency department; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit

Table

| Active ingredient | Total daily dose (microg) | ||

Low | Medium | High | |

| Fluticasone propionate | 100 (50 twice daily) | <8 years: >100–200 (e.g. 100 twice daily) | <8 years: >200 |

8–11 years: >100–250 (e.g. 100 twice daily or 125 twice daily) | 8–11 years: >250 | ||

| Ciclesonide | 80 | 160 | >160 |

| Budesonide | 100–200 | >200–400 | >400 |

| Beclometasone (extra-fine particle) | 50–100 | >100–200 | >200 |

Additional information

ICS: inhaled corticosteroid

[ ] Options recommended for first-line use in children, based on current evidence for efficacy and safety

Options not recommended as first-line treatment in children due to delivery device or concerns about systemic effects including potentially greater effects on growth

Usual doses (100 microg per actuation):

For cough or wheeze without visibly increased work of breathing: 2–4 actuations via pMDI plus spacer. If symptoms do not resolve within a few minutes, use 2 more actuations.

For increased work of breathing: 6–12 actuations via pMDI plus spacer. If symptoms do not resolve within a few minutes, use 6 more actuations.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

All children with asthma require a rapid-acting bronchodilator to manage symptoms as they occur, even if the child is also receiving ICS-based maintenance treatment. Salbutamol is currently the first-choice reliever for children younger than 12 years.

The use of spacers with pMDIs reduces oropharyngeal deposition, increases lung deposition, and minimises problems associated with poor coordination of actuation with inhalation with pMDIs.[Lavorini 2009] The use of a spacer with a pMDI may increase the response to SABA, compared with pMDIs and dry-powder inhalers.[Lavorini 2009]

Note on the 2025 recommendation: Anti-inflammatory reliever (ICS plus formoterol or ICS plus salbutamol in a single inhaler) is not approved by the TGA for use in children aged 6–11 years. Future Australian asthma handbook guidance may recommend anti-inflammatory reliever in place of salbutamol, depending on the findings of recent and ongoing clinical trials, and on TGA and PBS decisions.

For children 6–11 years not receiving maintenance ICS treatment, some guidelines recommend a low dose of ICS to be taken on each occasion that reliever is needed,[GINA 2025] based on two clinical trials of ICS and SABA in separate inhalers in children with asthma.[Martinez 2011, Sumino 2020] In one study, children using ICS plus SABA as needed had fewer exacerbations than those taking SABA alone as needed.[Martinez 2011] In the other, as-needed ICS plus SABA was as effective as daily maintenance low-dose ICS in controlling asthma symptoms and exacerbations.[Sumino 2020] However, this strategy may be impractical for many children and their parents/carers, because it requires use of two devices. The combination of an ICS and a SABA in a single inhaler is not available in Australia.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org.

Lavorini F, Fontana GA. Targeting drugs to the airways: The role of spacer devices. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2009; 6: 91-102.

Martinez FD, Chinchilli VM, Morgan WJ, et al. Use of beclomethasone dipropionate as rescue treatment for children with mild persistent asthma (TREXA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377: 650-657.

Sumino K, Bacharier LB, Taylor J, et al. A pragmatic trial of symptom-based inhaled corticosteroid use in African-American children with mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 176-185.e172.

Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne’s What is asthma? videos for parents, explaining how to identify wheeze and other signs, and how to correctly use a pMDI with spacer.

Higher salbutamol doses can be given when the child shows marked increase in work of breathing, severe dyspnoea and other signs of acute asthma, e.g. 12 actuations via pMDI plus spacer. If symptoms do not resolve within a few minutes, the dose is repeated.

Information on preparing written asthma action plans for children 6–11 years

Information on assessing and managing acute asthma in primary care or emergency departments.

When calculating canisters per year, allowing for multiple inhalers in use at the same time.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Consumption three or more canisters of salbutamol in a year indicates that the child’s asthma is poorly controlled. A large cohort study reported that, in children aged 6–11 years, prescription of three or more SABA canisters per year was associated with at least double the risk of subsequent exacerbations, compared with lower SABA prescribing.[Morgan 2023]

Morgan A, Maslova E, Kallis C, et al. Short-acting β2-agonists and exacerbations in children with asthma in England: SABINA Junior. ERJ Open Res 2023; 9: 00571-2022.

If symptoms are frequent (daytime symptoms twice per week or more, or night-time symptoms twice per month or more), symptoms are restricting activity or sleep, or the child has a history of an exacerbation treated with systemic corticosteroids in the past 12 months, begin a treatment trial with daily maintenance low-dose ICS, in addition to salbutamol as needed.

Review clinical response in 8–12 weeks.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Prevention of exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroid treatment is a key goal of asthma management. Treatment with inhaled corticosteroids is the main strategy available to reduce the risk of exacerbations.

The use of multiple short courses of oral corticosteroids to manage asthma exacerbations in children is associated with a dose-dependent reduction in bone mineral accretion and increased risk for osteopenia.[Kelly 2008]

Short course of systemic corticosteroids in adults are associated with increased lifetime risk of osteoporosis, pneumonia, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases, cataract, sleep apnoea, renal impairment, depression/anxiety, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain.[Price 2018]

Efficacy

Maintenance treatment with low doses of ICS significantly reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations in children. In a large 3-year clinical trial in children aged 5–10 years with recently diagnosed asthma, maintenance treatment with low-dose ICS (plus SABA as needed) reduced the risk of severe exacerbations by 40%, improved lung function, increased symptom-free days and decreased days lost from school years, compared with SABA only.[Chen 2006]

Safety

At recommended doses, ICSs are generally well tolerated in children.[Rachelefsky 2009; Kapadio 2016]

The use of a spacers with pMDIs reduces oropharyngeal drug deposition and therefore reduces the risk of local adverse effects (e.g. candidiasis and dysphonia) with ICS.[Lavorini 2020]

Topical effects of ICS can also be reduced by mouth-rinsing and spitting after inhaling. Immediate quick mouth-rinsing removes more residual medicine in the mouth than delayed rinsing.[Yokoyama 2007]

ICS-related systemic adverse effects in children include suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (rare),[Kapadio 2016] short-term linear growth suppression, clinically non-significant effects on bone mineral density, and dose-dependent effects on glucose metabolism.[Kapadio 2016]

A review of long-term clinical trials of recommended doses of inhaled corticosteroids in children found little or no effect on measures of HPA axis function over 12 to 36 months follow-up, and no clinically significant effects on bone mineral density.[Pedersen 2006]

Regular use of ICS in children before puberty is associated with an average reduction of 0.48 cm/year in linear growth rate in the first year of treatment, after which less effect is seen. Growth suppression depends on the dose.[Axelsson 2019] Fluticasone propionate may have a lesser effect on growth rate than beclometasone or budesonide, when administered at an equivalent dose.[Axelsson 2019]

Uncontrolled asthma also reduces children’s growth and final adult height.[Pedersen 2001]

Axelsson I, Naumburg E, Prietsch SO, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in children with persistent asthma: effects of different drugs and delivery devices on growth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 6: CD010126.

Chen YZ, Busse WW, Pedersen S, et al. Early intervention of recent onset mild persistent asthma in children aged under 11 yrs: the Steroid Treatment As Regular Therapy in early asthma (START) trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2006; 17(Suppl 17): 7-13.

Kapadia CR, Nebesio TD, Myers SE, et al. Drugs and Therapeutics Committee of the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Endocrine effects of inhaled corticosteroids in children. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170: 163-170.

Kelly HW, Van Natta ML, Covar RA, et al. Effect of long-term corticosteroid use on bone mineral density in children: a prospective longitudinal assessment in the childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) study. Pediatrics 2008; 122: e53-e61.

Lavorini F, Barreto C, van Boven JFM, et al. Spacers and valved holding chambers – the risk of switching to different chambers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020; 8: 1569-1573.

Pedersen S. Do inhaled corticosteroids inhibit growth in children? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 521-35.

Pedersen S. Clinical safety of inhaled corticosteroids for asthma in children: an update of long-term trials. Drug Saf 2006; 29: 599-612.

Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy 2018; 11: 193-204.

Rachelefsky G. Inhaled corticosteroids and asthma control in children: assessing impairment and risk. Pediatrics. 2009; 123: 353-366.

Yokoyama H, Yamamura Y, Ozeki T, et al. Effects of mouth washing procedures on removal of budesonide inhaled by using Turbuhaler. Yakugaku Zasshi 2007; 127: 1245-1249.

Note on the 2025 recommendation: Anti-inflammatory reliever (ICS plus formoterol or ICS plus salbutamol in a single inhaler) is not approved by the TGA for use in children aged 6–11 years. Future Australian asthma handbook guidance may recommend anti-inflammatory reliever in place of salbutamol or daily maintenance treatment with low-dose ICS, or MART as an alternative to maintenance ICS, depending on the findings of clinical trials now underway and on TGA and PBS decisions.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

The use of nebulisers is not recommended. Delivery of inhaled medicines by nebuliser is unnecessary,[Cates 2013] except in some patients with severe acute asthma unable to breathe through a spacer.

Nebulisers may transmit respiratory viruses.[Hui 2009]

In children and adults, the use of nebulisers for SABA is associated with a higher risk of exacerbations than the use of inhalers.[Paris 2008]

Nebulised salbutamol is associated with more systemic adverse effects than pMDIs. In studies of children with acute asthma, higher rates of tremor have been reported among children treated with nebulised salbutamol than salbutamol via pMDI with spacer.[Cates 2013] Nebulised ICS can damage the child’s eyes if the face mask is not well fitted, and can cause rash and atrophy of skin around the nose and mouth.[GINA 2025]

The use of home nebulisers could also lead to delays in treatment, compared with the prompt use of readily transportable pMDIs anywhere outside the home, whenever the child has asthma symptoms.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org

Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 9: CD000052.

Hui DS, Chow BK, Chu LC, et al. Exhaled air and aerosolized droplet dispersion during application of a jet nebulizer. Chest 2009; 135: 648-654

Paris J, Peterson EL, Wells K, et al. Relationship between recent short-acting beta-agonist use and subsequent asthma exacerbations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101: 482-487.

Recommendation type: Adapted from GINA

Oral bronchodilators are not recommended for any age group. Oral salbutamol has a longer onset of action and a higher rate of adverse effects than inhaled salbutamol.[GINA 2025]

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org

Recommendation type: Adapted from GINA

Oral bronchodilators are not recommended for any age group.[GINA 2025]

Theophylline is less effective than inhaled bronchodilators in reducing symptoms and increasing lung function, and adverse effects are common.[Morali 2001, ALAACRC 2007, Barnes 2013]

American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers. Clinical trial of low-dose theophylline and montelukast in patients with poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 235-242.

Barnes PJ. Theophylline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 901-906.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org

Morali T, Yilmaz A, Erkan F, et al. Efficacy of inhaled budesonide and oral theophylline in asthmatic subjects. J Asthma 2001; 38: 673-679.

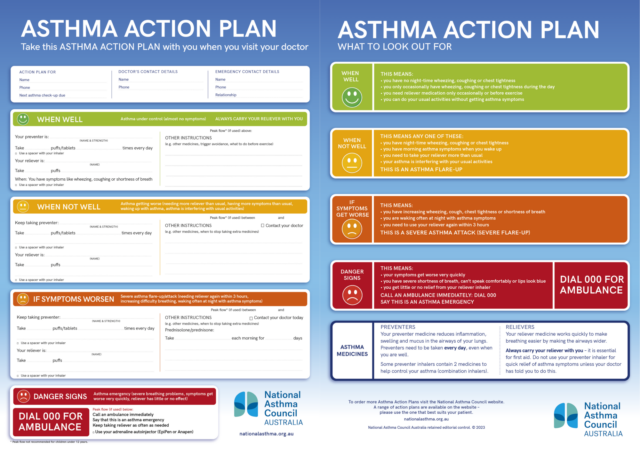

Make sure parents understand how to follow the instructions. Advise parents to give a copy to the child’s school and any other carers.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Every child with asthma should have their own written asthma action plan for parents to follow when symptoms worsen.

In children aged 6 years and over, the use of written asthma action plans significantly reduces the rate of visits to acute care facilities, the number of school days missed and night-time waking, and improves symptoms.[Zemek 2008] For children, written asthma action plans that are based on symptoms appear to be more effective than action plans based on peak expiratory flow monitoring.[Zemek 2008]

Zemek RL, Bhogal S, Ducharme FM. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining written action plans in children – What is the plan? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008; 162: 157-163.

National Asthma Council Australia’s Library of asthma action plan templates

Schools in all Australian states and territories require parents or carers of children with asthma to provide a written asthma action plan stating the child’s known asthma triggers and instructions to be followed if symptoms occur, and emergency procedures in the event of an asthma exacerbation.

Information on asthma action plans for children 6–11 years

For example, salbutamol 200 microg: two separate actuations via pMDI (100 microg/actuation) and spacer.

Recommendation type: Adapted from GINA

Salbutamol taken 15 minutes before exercise is effective in preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Grandinetti 2024, Weiler 2016]

ICS treatment prevents or reduces the risk of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children.[Koh 2007, Visser 2015]

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org.

Grandinetti R, Mussi N, Rossi A, et al. Exercise-Induced bronchoconstriction in children: state of the art from diagnosis to treatment. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 4558.

Koh MS, Tee A, Lasserson TJ. Inhaled corticosteroids compared to placebo for prevention of exercise induced bronchoconstriction Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; CD002739.

Weiler JM, Brannan JD, Randolph CC, et al. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction update–2016. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138: 1292-1295.e36.

Visser R. Wind M, de Graaf B. Protective effect of a low single dose inhaled steroid against exercise induced bronchoconstriction Pediatr Pulmonol 2015; 50: 1178-1183.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is very common in children with asthma. Symptoms include cough, dyspnea, wheezing, chest tightness, increased mucus production, and heightened respiratory effort.[Grandinetti 2024]

Exercise-induced asthma symptoms should be managed by achieving good overall asthma control with ICS-based treatment if indicated, pre-emptive use of rapid-acting bronchodilators before exercise, and general advice on avoidance (warming up before intensive exercise, avoiding air pollution and cold dry air).[Grandinetti 2024]

When assessing reliever as a component of asthma symptom control assessment, do not include reliever doses taken pre-emptively before exercise.[GINA 2025]

Information on exercise and asthma

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

In school-aged children with asthma, sensitisation to aeroallergens (confirmed by skin-prick testing) and raised IgE is associated with greater benefit from ICS treatment (greater reduction in risk of exacerbations and greater increase in symptom control), compared with non-atopic children.[Gerald 2015, Szefler 2010]

Gerald JK, Gerald LB, Vasquez MM, et al. Markers of differential response to inhaled corticosteroid treatment among children with mild persistent asthma [published correction appears in J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 793]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 540-546.e3.

Szefler SJ, Martin RJ. Lessons learned from variation in response to therapy in clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 125: 285-294.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Montelukast monotherapy is generally less effective than ICS or ICS-LABA in preventing asthma exacerbations.[Chauhan 2012, Cividini 2023]

Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Anti-leukotriene agents compared to inhaled corticosteroids in the management of recurrent and/or chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 5: CD002314.

Cividini S, Sinha I, Donegan S, et al. Best step-up treatments for children with uncontrolled asthma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of individual participant data. Eur Respir J 2023; 62: 2301011.

Recommendation type: Adapted from CICADA 2024

In children, chronic cough in the absence of other symptoms/signs is rarely due to asthma.[Marchant 2024]

Cough that is due to asthma typically improves after 2–4 weeks of treatment with ICS. [Marchant 2024]

Australian cough management guidelines recommend against the use of ICS to manage chronic cough in children unless there are specific features to suggest asthma, and that ICS should be ceased if cough does not resolve within 4 weeks.[Marchant 2024]

Marchant JM, Chang AB, Kennedy E, et al. Cough in Children and Adults: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management (CICADA). Summary of an updated position statement on chronic cough in Australia. Med J Aust 2024; 220: 35-45.

Intranasal corticosteroid (alone or in combination with antihistamine) is first-choice treatment for allergic rhinitis in children 6–11 years.

It is indicated even if the child is also using low-dose maintenance ICS for asthma.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Intranasal corticosteroids are effective in the treatment of seasonal or perennial allergic rhinitis [Brożek 2017] and are recommended in international guidelines.[GINA 2025, Brożek 2017]

Systemic absorption of intranasal corticosteroids is negligible in children, but total corticosteroid dose and potential effects should be monitored.[ASCIA 2024]

Montelukast is approved as treatment for both asthma and allergic rhinitis,[Australia PI: montelukast] but it is less effective than ICS for asthma [Cividini 2023, Chauhan 2012] less effective than intranasal corticosteroids for allergic rhinitis,[Krishnamoorthy 2020] and has been associated with neuropsychiatric disorders in all age groups.[TGA 2018]

(see TGA safety alert).

The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends that specific allergen immunotherapy can be considered for children over 5 years.[ASCIA 2024]

ASCIA. Aeroallergen Immunotherapy. A guide for clinical immunology/allergy specialists. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy, 2024.

Australian product information – Singulair (montelukast sodium). [Revised 13 January 2021] Therapeutic Goods Administration (www.ebs.tga.gov.au)

Brożek JL, Bousquet J, Agache I, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines-2016 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 950-958.

Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Anti-leukotriene agents compared to inhaled corticosteroids in the management of recurrent and/or chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 5: CD002314.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org.

Krishnamoorthy M, Mohd Noor N, et al. Efficacy of montelukast in allergic rhinitis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs 2020; 80: 1831-1851.

National Asthma Council Australia’s Allergic rhinitis treatment planner

The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne’s allergic rhinitis management guide for primary care

Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy’s allergen immunotherapy guide for clinical immunology/allergy specialists

Explain that:

Medication management

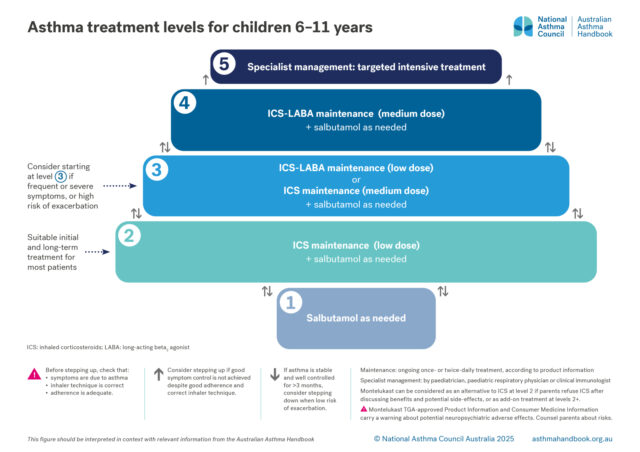

Treatment options for primary school-aged children, classified according to the intensity of treatment needed to…

Clinical topics

Information on exercise-induced asthma symptoms in children and adults and asthma management for elite athletes.

Principles of management

Goals and principles of asthma management in primary school-aged children.