Australian Asthma Handbook

The National Guidelines for Health Professionals

Cite

Table

| Mild–moderate | Severe | Life-threatening | |

Assessment

| All of: Can walk, speak whole sentences in one breath SpO2 (room air) >94% | Any of: Unable to complete sentences in one breath due to breathlessness Use of accessory muscles of neck or intercostal muscles/tracheal tug/subcostal recession during inspiration Obvious respiratory distress SpO2 (room air) ≤94% | Any of: Reduced consciousness/collapse, exhaustion/confused/agitated Cyanosis Poor respiratory effort SpO2 (room air) <92% Poor respiratory effort, soft/absent breath sounds

|

Immediate treatment | Give salbutamol 4–12 actuations (100 microg per actuation) via pMDI and spacer (tidal breathing) | Start bronchodilators: Salbutamol 12 actuations (100 microg per actuation) via pMDI and spacer (tidal breathing). If patient cannot use spacer, give 5 mg nebule via nebuliser. Ipratropium 8 actuations (21 microg/actuation) via pressurised metered-dose inhaler and spacer every 20 minutes for first hour. Start oxygen supplementation if SpO2 <92% on room air and titrate to target 92–96% (or 88–92% if risk of hypercapnoea) | Arrange immediate transfer to higher-level care Start bronchodilators: Salbutamol 2 x 5 mg nebules via continuous nebulisation driven by oxygen Ipratropium 500 microg added to nebulised solution every 20 minutes for first hour. Maintain SpO2 92–96% (or 88–92% if risk of hypercapnoea)

|

| Continued treatment | Repeat salbutamol 4–12 actuations every 20 minutes for the first hour, if needed (sooner if needed). Then reduce to every 4–6 hours, if needed | Repeat salbutamol 12 actuations every 20 minutes for the first hour (sooner if needed) Repeat bronchodilators 4–6 hourly for 24 hours. If salbutamol delivered via nebuliser, add 500 microg ipratropium to nebulised solution every 20 minutes for first hour. Repeat 4–6 hourly. | Repeat bronchodilators 4–6 hourly. When dyspnoea improves, consider changing to salbutamol via pMDI plus spacer or intermittent nebuliser |

Additional information

SpO2: oxygen saturation

Table

| Mild–moderate (all of): | Severe (any of): | Life-threatening (any of): | |

| Consciousness | Alert | N/A | Unconscious, drowsy, confused or agitated |

| Speech | Can finish a sentence in one breath | Can only speak a few words in one breath | Cannot speak |

| Posture | Can walk, sit up straight, lie flat | Unable to lie flat due to dyspnoea Sitting hunched forward | Collapsed or exhausted |

| Breathing | Respiratory distress is not severe | Paradoxical chest wall movement or Use of accessory muscles of neck or intercostal muscles during inspiration or Subcostal recession | Severe respiratory distress or Poor respiratory effort |

| Skin colour | Normal | N/A | Cyanosis |

| Respiratory rate | <25 breaths/min | ≥25 breaths/min | Bradypnoea (indicates respiratory exhaustion) |

| Heart rate | <110 beats/min | ≥110 beats/min | Cardiac arrhythmia or Bradycardia (may occur just before respiratory arrest) |

| Chest auscultation | Wheeze or Normal lung sounds

| N/A | Silent chest or Reduced air entry |

| Oxygen saturation (pulse oximetry on room air) | >96% | 92–96% | <92% or Clinical cyanosis |

| Blood gas analysis (adults, if performed) | Not indicated | Not indicated | PaO2 <60 mmHg PaCO2 >50 mmHg(a) PaCO2 within normal range despite low PaO2 pH <7.35(b) |

| FEV1 | > 50% predicted or personal best | ≤50% predicted or personal best | Spirometry not feasible |

Additional information

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second measured by spirometry; N/A: Not applicable – may be the same as moderate and does not determine severity category; PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood

a. The presence of hypercapnoea indicates that the patient is tiring and may need ventilatory support

b. Metabolic acidosis may occur with high-dose salbutamol and with increased work of breathing

Table

| Option 1: Inhaled corticosteroid–formoterol combination as maintenance-and-reliever therapy | |||||

| Combination and strength* | Maintenance dose† | Reliever dose | Maximum total inhalations in any single day‡ | ||

| Budesonide 200 microg + formoterol 6 microg via DPI (Symbicort Turbuhaler, Rilast Turbuhaler, DuoResp Spiromax) | 2 inhalations twice daily | 1 inhalation – can be repeated after a few minutes if symptoms persist. Maximum 6 inhalations at any one time (rarely needed) | 12 | ||

| Beclometasone 100 microg + formoterol 6 microg via pMDI (Fostair) – adults ≥18 years only | 2 inhalations twice daily | 1 inhalation via spacer – can be repeated after a few minutes if symptoms persist. Maximum 6 inhalations at any one time (rarely needed) | 8 | ||

| Budesonide 100 microg + formoterol 3 microg via pMDI (Symbicort Rapihaler, Rilast Rapihaler) | 4 inhalations twice daily | 2 inhalations (1 at a time) via spacer – can be repeated after a few minutes if symptoms persist. Maximum 12 inhalations at any one time (rarely needed) | 24 | ||

pMDI: pressurised metered-dose inhaler; DPI: dry powder inhaler; MART: maintenance-and-reliever therapy *Lower doses are available but not suitable after recent severe exacerbation. Note: ICS-formoterol cannot be used as reliever for patients receiving maintenance treatment with a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and any long-acting beta2 agonist other than formoterol. †Short-term use after severe exacerbation ‡ Includes maintenance doses and extra doses taken for relief of symptoms. Note: very few patients need the maximum permitted number of inhalations in one day | |||||

| Option 2. Inhaled corticosteroid (alone or in combination with long-acting beta2 agonist) | |||||

Total daily dose (microg/day) | |||||

| Low | Medium | High | |||

| Not adequate after severe exacerbation | Recommended at discharge | If severe or life-threatening acute asthma | |||

| Beclometasone dipropionate | 100–200 | 250–400 | >400 | ||

| Budesonide | 200–400 | 500–800 | >800 | ||

| Ciclesonide | 80–160 | 240–320 | >320 | ||

| Fluticasone furoate (once/day only) | – | 100 | 200 | ||

| Fluticasone propionate | 100–200 | 250–500 | >500 | ||

Note: Prescribe at least medium-dose inhaled corticosteroid (in combination with a long-acting beta2 agonist) in the short term for adults and adolescents being discharged after a severe exacerbation. The patient also uses a short-acting beta2 agonist (salbutamol or terbutaline) as needed to relieve symptoms | |||||

Additional information

Suggested short-term preventive treatment for adults and adolescents after a severe asthma exacerbation, in addition to oral corticosteroids as indicated

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Routine objective assessment of oxygen saturation with pulse oximetry at initial assessment of acute asthma is needed because clinical signs may not correlate with hypoxaemia.[Barnett 2022]

Barnett A, Beasley R, Buchan C, et al. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand position statement on acute oxygen use in adults: 'Swimming between the flags'. Respirology 2022; 27: 262-276.

Shi C, Goodall M, Dumville J, et al. The accuracy of pulse oximetry in measuring oxygen saturation by levels of skin pigmentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2022; 20: 267.

Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand’s position statement on acute oxygen use in adults

Perform the assessment while preparing to administer salbutamol (and oxygen, if needed).

Pulse oximetry may overestimate oxygen saturation in people with higher levels of skin pigmentation.[Shi 2022]

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Repeated administration of inhaled SABA every 20 minutes for the first hour is effective for rapidly achieving bronchodilation in patients with mild or moderate asthma exacerbations.[GINA 2025]

Among patients with acute asthma who do not require mechanical ventilation, salbutamol delivered via a pMDI with spacer is at least as effective as salbutamol delivered via nebuliser in adults.[Cates 2006, Dhuper 2011]

The use of nebulisers may increase the risk of viral transmission.[Hui 2009, Biney 2024, Goldstein 2021] Healthcare workers should follow infection control procedures including use of personal protective equipment such as face masks.

Oral salbutamol or intravenous salbutamol are not recommended.

In adults and older adolescents with severe acute asthma treated in the emergency department, the combination of ipratropium and short-acting beta2 agonist reduces hospitalisation rate and improves lung function, compared with short-acting beta2 agonist alone. [Kirkland 2017]

In adults, the combination of ipratropium and short-acting beta2 agonist is associated with a higher rate of adverse effects (e.g. tremor, agitation, and palpitations) than short-acting beta2 agonist alone. [Kirkland 2017]

Biney IN, Ari A, Barjaktarevic IZ, et al. Guidance on mitigating the risk of transmitting respiratory infections during nebulization by the COPD Foundation Nebulizer Consortium. Chest 2024; 165: 653-668.

Cates CJ, Crilly JA, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; Issue 2: CD000052.

Dhuper S, Chandra A, Ahmed A, et al. Efficacy and cost comparisons of bronchodilatator administration between metered dose inhalers with disposable spacers and nebulizers for acute asthma treatment. J Emerg Med 2011; 40: 247-55.

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2025. Available from: www.ginasthma.org

Goldstein KM, Ghadimi K, Mystakelis H, et al. Risk of transmitting coronavirus disease 2019 during nebulizer treatment: a systematic review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2021; 34: 155-170.

Hui DS, Chow BK, Chu LC, et al. Exhaled air and aerosolized droplet dispersion during application of a jet nebulizer. Chest 2009; 135: 648-654.

Kirkland SW, Vandenberghe C, Voaklander B et al. Combined inhaled beta-agonist and anticholinergic agents for emergency management in adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; Issue 1: CD001284.

National Asthma Council Australia’s video on how to use a metered dose inhaler (puffer) with a spacer for adults

National Asthma Council Australia’s fact sheet on spacers for pressurised metered-dose inhalers

Tidal breathing method:

1. Connect spacer to pMDI and tell patient to seal lips firmly around spacer mouthpiece.

2. Shake the inhaler well

3. Release 1 actuation of salbutamol into the spacer.

4. Tell the patient to breathe in and out for four breaths while keeping lips sealed around mouthpiece.

Repeat process until all required actuations delivered, shaking inhaler again before each actuation then releasing 1 actuation into the spacer at a time before patient inhales.

If the person cannot seal their lips tightly around the spacer mouthpiece, use a tightly fitting adult mask connected to the spacer mouthpiece.

If the patient cannot breathe through a spacer using either the mouthpiece or a mask, use a nebuliser with mask.

The tidal breathing technique should only be used while the patient is too breathless to use the standard single-breath technique. Once breathing improves, consider switching to single-breath technique.

Use a cardboard disposable spacer or a new spacer afterwards given to the patient.

Follow current guidance in Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand’s position statement on acute oxygen use in adults.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Hypoxia is associated with life-threatening asthma.

Oxygen should be administered if SpO2 while breathing room air is less than 92%, and titrated to a target SpO2 range of 92–96% for patients not considered to be at risk of hypercapnoea.[Barnett 2022]

Current Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand guidance recommends a SpO2 target of 88–92% for patients with exacerbations of COPD, asthma, or other conditions associated with chronic respiratory failure, including obesity, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, neuromuscular disease, and chest wall deformities (e.g. severe kyphoscoliosis).[Barnett 2022]

The aim of titrated oxygen therapy in acute care is to achieve adequate oxygen saturation without causing hypercapnoea.[Barnett 2022] Adults with acute asthma and those with both asthma and COPD are at greater risk of hypercapnoeic respiratory failure.[Barnett 2022]

Perform blood gas analysis in patients with severe or life-threatening acute asthma or if hypercapnoea is suspected.[Barnett 2022]

Barnett A, Beasley R, Buchan C, et al. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand position statement on acute oxygen use in adults: 'Swimming between the flags'. Respirology 2022; 27: 262-276.

Hodder R, Lougheed MD, Rowe BH, et al. Management of acute asthma in adults in the emergency department: nonventilatory management. CMAJ 2010; 182: E55-67.

Shi C, Goodall M, Dumville J, et al. The accuracy of pulse oximetry in measuring oxygen saturation by levels of skin pigmentation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2022; 20: 267.

Pulse oximetry may overestimate oxygen saturation in people with higher levels of skin pigmentation.[Shi 2022]

Perform a physical examination including vital signs.

Monitor pulse oximetry.

Perform chest auscultation. Look for signs of complications, pneumothorax or consolidation.

Obtain blood gas analysis if patient presented with life-threatening acute asthma or as indicated.

Obtain a chest radiograph to detect the presence of pneumothorax, consolidation or evidence of cardiac failure.

Obtain spirometry when the patient is able to perform the test.

Complete a brief history, including:

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

The association of asthma and food allergy is a risk factor for fatal and near-fatal allergic reactions to food allergens.[Burks 2012]

Burks AW, Tang M, Sicherer S, et al. ICON: food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129: 906-920.

Systemic corticosteroids are indicated for all severe and life-threatening acute asthma exacerbations in adults and adolescents, and should be considered for mild–moderately severe exacerbations on a case-by-case basis.

Adults:

Oral prednisone/prednisolone 37.5–50 mg, then repeat each morning on second and subsequent days (total 5–10 days)

Alternative: oral dexamethasone 16 mg for 2 days then cease

Adolescents:

Oral prednisone/prednisolone 1 mg/kg (maximum 50 mg) once daily for 3–5 days

Alternative: oral dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg as a single dose (can be repeated on the following day if needed)

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

In adults and adolescents with acute asthma, systemic corticosteroids given within 1 hour of presentation to an emergency department reduce the need for hospital admission.[Rowe 2001]

Prednisone/prednisolone doses for adults are based on studies conducted in patients with asthma exacerbations presenting in emergency departments.[Rowe 2001, Rowe 2007, Rowe 2017] Doses for adolescents are based on studies in children.[Normansell 2016, Chang 2008]

It is not necessary to taper the dose after a short course of oral prednisone/prednisolone.[Rowe 2017, O’Driscoll 1993, Cydulka 1998]

Oral dexamethasone is as effective as prednisone/prednisolone in adults and children [Rowe 2017, Normansell 2016, Rowe 2007] Studies evaluating oral dexamethasone in adults have used a single dose of 12 mg [Rehrer 2016] or 16 mg on 2 consecutive days. [Kravitz 2011] Dexamethasone has a longer half-life than prednisone/prednisolone. Longer courses may have more pronounced mineralocorticoid adverse effects. Oral dexamethasone treatment for acute asthma need not exceed 2 days.

In adults, an oral or intramuscular corticosteroid course of at least 7 days appears more effective than a shorter course in preventing relapse within 10 days of discharge after acute asthma,[Rowe 2017] although one clinical trial evaluating prednisone reported that 5 days was as effective as 10 days.[Jones 2002]

Safety

Short-term adverse effects: short courses use of oral corticosteroids to treat acute asthma are often well tolerated in adults,[Rowe 2001, Rowe 2007] but patients may report mood changes, gastrointestinal disturbances,[Berthon 2015] nocturia, or difficulty sleeping.

In patients with diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, blood glucose monitoring (e.g. morning and evening samples) may be indicated during treatment with oral corticosteroids.

Long-term adverse effects: short courses of oral corticosteroids to manage asthma exacerbations are associated with increased lifetime risk of osteoporosis, pneumonia, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases, cataract, sleep apnoea, renal impairment, depression/anxiety, type 2 diabetes, and weight gain. [Price 2018] Repeated use for asthma exacerbations should prompt review of management; consider referral to a respiratory physician for assessment.

Berthon BS, Gibson PG, McElduff P et al. Effects of short-term oral corticosteroid intake on dietary intake, body weight and body composition in adults with asthma – a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy 2015; 45: 908-19.

Cydulka RK, Emerman CL. A pilot study of steroid therapy after emergency department treatment of acute asthma: is a taper needed?. J Emerg Med 1998; 16: 15-19.

Jones AM, Munavvar M, Vail A, et al. Prospective, placebo-controlled trial of 5 vs 10 days of oral prednisolone in acute adult asthma. Respir Med 2002; 96: 950-954.

Kravitz J, Dominici P, Ufberg J, et al. Two days of dexamethasone versus 5 days of prednisone in the treatment of acute asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 58: 200-204.

Normansell R, Kew KM, Mansour G. Different oral corticosteroid regimens for acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; Issue 5: CD011801.

O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, et al. Double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. Lancet 1993; 341: 324-327.

Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy 2018; 11: 193-204.

Rehrer MW, Liu B, Rodriguez M et al. A randomized controlled noninferiority trial of single dose of oral dexamethasone versus 5 Days of oral prednisone in acute adult asthma. Ann Emerg Med 2016; 68: 608-13.

Rowe BH, Kirkland SW, Vandermeer B et al. Prioritizing systemic corticosteroid treatments to mitigate relapse in adults with acute asthma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med 2017; 24: 371-81.

Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme F, et al. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; Issue 1: CD002178.

Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme F, et al. Corticosteroids for preventing relapse following acute exacerbations of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; Issue 3: CD000195.

If corticosteroids cannot be given orally, an alternative route (e.g. IV hydrocortisone) can be used. Switch to oral prednisolone when possible.

Dispense only one course, to avoid overuse or inappropriate use of systemic corticosteroids.

If dyspnoea/increased work of breathing is partially relieved within the first 5 minutes, reassess the need for repeated bronchodilator at 15 minutes.

If dyspnoea/increased work of breathing is not relieved, or condition deteriorates, repeat bronchodilator dose and consider adding inhaled ipratropium bromide (if not part of initial treatment) or IV magnesium sulfate.

Inhaled ipratropium bromide:

Adults and adolescents: 8 actuations (21 microg/actuation) via pressurised metered-dose inhaler and spacer every 20 minutes for first hour. Repeat 4–6 hourly for 24 hours

Intravenous magnesium sulfate:

Adults and adolescents: 0.2 mmol/kg (maximum 10 mmol) diluted in a compatible solution as a single IV infusion over 20 minutes

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Ipratropium bromide: Ipratropium is recommended as a first-line bronchodilator for patients with severe or life-threatening acute asthma, and as a second-line bronchodilator if inadequate response to salbutamol.

In adults and older adolescents with severe acute asthma treated in the emergency department, the combination of ipratropium and short-acting beta2 agonist reduces hospitalisation rate and improves lung function, compared with short-acting beta2 agonist alone.[Kirkland 2017] Hospitalisation rates are not reduced in patients with mild or moderate acute asthma.[Kirkland 2017]

In adults, the combination of ipratropium and short-acting beta2 agonist is associated with a higher rate of adverse effects (e.g. tremor, agitation, and palpitations) than short-acting beta2 agonist alone.[Kirkland 2017]

Intravenous magnesium sulfate

Intravenous magnesium sulfate can be considered as a second-line bronchodilator in severe or life-threatening acute asthma, or when poor response to repeated maximal doses of other bronchodilators. It should not be used as a substitute for inhaled beta2 agonists.[Knightly 2017]

In adults, intravenous magnesium sulfate magnesium sulfate may reduce hospital admissions and may improve lung function in adults with acute asthma who have failed to respond to standard treatment.[Green 2016, Kew 2014] In a large, well-conducted randomised controlled trial in adults with moderate-to-severe acute asthma treated in an emergency department (excluding those with life-threatening asthma), intravenous magnesium sulfate improved dyspnoea scores but did not reduce hospital admission rates.[Su 2018]

The optimal dose and infusion regimen has not been identified.[Green 2016]

IV magnesium sulfate IV appears to be well tolerated in adults.[Green 2016] Minor flushing is the most common adverse event.[Green 2016] Other adverse effects reported in clinical trials include fatigue, nausea, headache and hypotension. [Kew 2014]

Nebulised magnesium sulfate

Nebulised magnesium sulfate is not recommended for acute asthma.

In adults with non-life-threatening acute asthma, addition of nebulised magnesium sulfate does not appear to reduce hospitalisation or dyspnoea rates, compared with standard therapy alone.[Kew 2014, Goodacre 2014] There is low-certainty evidence that nebulised MgSO4 as an add-on second-line therapy for adolescents and children with acute asthma may slightly improve lung function but does not reduce hospitalisation rates.[Kumar 2024]

Nebulised magnesium sulfate is well tolerated and does not appear to be associated with an increase in serious adverse events.[Knightly 2017]

Goodacre S, Cohen J, Bradburn M et al. Intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate versus standard therapy for severe acute asthma (3Mg trial): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013; 1: 293-300.

Goodacre S, Cohen J, Bradburn M et al. The 3Mg trial: a randomised controlled trial of intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate versus placebo in adults with acute severe asthma. Health Technol Assess 2014; 18: 1-168.

Green RH. Asthma in adults (acute): magnesium sulfate treatment. BMJ Clin Evid 2016; 2016: 1513.

Kew KM, Kirtchuk L, Michell CI. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for treating adults with acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014: CD010909.

Kirkland SW, Vandenberghe C, Voaklander B et al. Combined inhaled beta-agonist and anticholinergic agents for emergency management in adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; Issue 1: CD001284.

Knightly R, Milan SJ, Hughes R et al. Inhaled magnesium sulfate in the treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 11: CD003898.

Kumar J, Kumar P, Goyal JP, et al. Role of nebulised magnesium sulfate in treating acute asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024; 8: e002638.

Su Z, Li R, Gai Z. Intravenous and nebulized magnesium sulfate for treating acute asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018; 34: 390-395.

National Asthma Council’s video on how to use a metered dose inhaler (puffer) with a spacer for adults

National Asthma Council Australia’s fact sheet on spacers for pressurised metered-dose inhalers

The tidal breathing technique should only be used while the patient is too breathless to use the standard single-breath technique. Once breathing improves, consider switching to single breath technique with breath.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Discharge treatment should include either of the following:

If the patient’s previous treatment was ICS-formoterol as needed or as maintenance-and-reliever therapy (MART), discharge on medium-dose MART. Do not replace the patient’s combination reliever with salbutamol reliever.

Provide written instructions on what to do if symptoms recur.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

ICS is essential, even if the patient has been prescribed a short course of systemic corticosteroid.

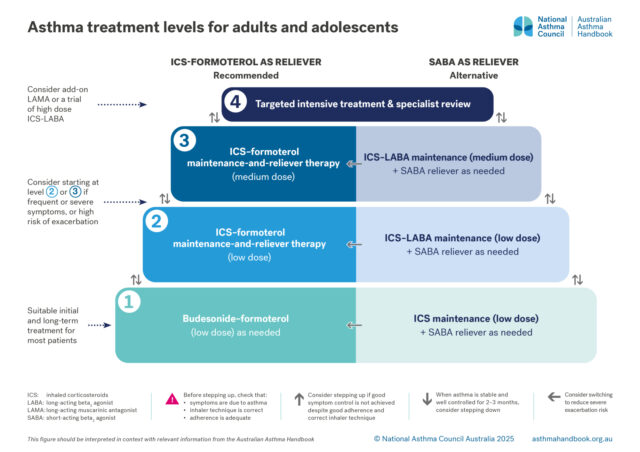

More information on asthma treatment regimens for adults and adolescents

Recheck within 3 days with the patient’s usual GP

Comprehensive assessment in 2–4 weeks to reassess risk factors and review the treatment regimen (GP or respiratory physician)

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Patients >12 years or >50 kg: adrenaline 300 microg IM via auto-injector

Recommendation type: Adapted from ASCIA 2024

Anaphylaxis should be suspected when asthma-like respiratory symptoms are accompanied by either of the following features: [ASCIA 2024]

ASCIA. Acute management of anaphylaxis. 2024, Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy.

ASCIA Guidelines: Acute management of anaphylaxis

Adrenaline should be given before considering salbutamol when anaphylaxis is suspected.[ASCIA 2024]

When breathing improves, consider changing to a pressurised metered-dose inhaler plus spacer or intermittent nebuliser.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Biney IN, Ari A, Barjaktarevic IZ, et al. Guidance on mitigating the risk of transmitting respiratory infections during nebulization by the COPD Foundation Nebulizer Consortium. Chest 2024; 165: 653-668.

Goldstein KM, Ghadimi K, Mystakelis H, et al. Risk of transmitting coronavirus disease 2019 during nebulizer treatment: a systematic review. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2021; 34: 155-170.

Hui DS, Chow BK, Chu LC, et al. Exhaled air and aerosolized droplet dispersion during application of a jet nebulizer. Chest 2009; 135: 648-654.

Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand’s position statement on acute oxygen use in adults

To deliver intermittent nebulised bronchodilators in a patient receiving oxygen therapy, use an air-driven compressor nebuliser and administer oxygen by nasal cannulae.

Titrate oxygen to target SpO2 92–96% in adults (or 88–92% if risk of hypercapnoea).

If nebulised salbutamol is needed for a patient receiving supplemental oxygen, the nebuliser can be driven by piped oxygen or an oxygen cylinder fitted with a high-flow regulator capable of delivering >6 L/min. The patient should be changed back to their original oxygen mask once nebulisation is complete.

The use of nebulisers may increase the risk of viral transmission.[Hui 2009, Biney 2024, Goldstein 2021] Healthcare workers should follow infection control procedures including use of personal protective equipment such as face masks.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Adrenaline is not used routinely in the management of severe acute asthma.

Its use should be reserved for situations where inhaled salbutamol cannot be given in a patient with respiratory arrest or pre-arrest status, or when anaphylaxis is suspected. IV administration can be considered if response to repeated IM doses and volume expansion is inadequate.

Evidence for outcomes with adrenaline is mainly from clinical trials conducted before 2000.[Baggott 2022] There is insufficient evidence to determine whether inhaled salbutamol is more effective than adrenaline as first-line treatment in the management of severe acute asthma, due to high risk of bias in published clinical trials and significant heterogeneity, including differences in study design.[Baggott 2022] Available evidence suggests adrenaline may be more effective in adults than in children.[Baggott 2022]

Low-quality evidence suggests that adrenaline is associated with higher rates of agitation, tremor and headache than inhaled salbutamol. [Baggott 2022]

There is also insufficient evidence to determine whether intramuscular adrenaline, given in addition to inhaled salbutamol, is more effective than inhaled salbutamol alone.[Baggott 2022]

Ambulance Victoria. Clinical practice guidelines. Version 3.12.15 (2024).

Baggott C, Hardy JK, Sparks J, et al. Epinephrine (adrenaline) compared to selective beta-2-agonist in adults or children with acute asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2022; 77: 563-572.

International asthma guidelines recommend inhaled salbutamol as the primary bronchodilator in acute asthma, and do not recommend the use of adrenaline except for patients with concomitant acute asthma and anaphylaxis or angioedema.[Baggott 2022] However, intramuscular adrenaline in addition to inhaled SABA is included in ambulance guidelines for prehospital management of acute asthma in some jurisdictions,[Baggott 2022] including in some Australian states. [Ambulance Victoria 2024]

Manage acute asthma in pregnant women as for other adults. Prescribe oral corticosteroids if indicated.

Recommendation type: Consensus recommendation

Consider admission if any of the following:

Include:

Principles of management

Goals and principles of asthma management in adults and adolescents.

Medication management

Recommended and alternative treatment options for patients 12 years and over, according to intensity of treatment…

Guide to asthma medicines, including types of treatment regimens, brand names, single-inhaler combinations, and inhaler…