Australian Asthma Handbook

The National Guidelines for Health Professionals

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is common in people with asthma. Optimal treatment of asthma reduces the frequency and severity of exercise-induced symptoms.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is characterised by coughing, dyspnoea, wheezing, or chest tightness after exercise.

Symptoms of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction typically peak after, not during, exercise.

Frequent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction may indicate poor asthma control.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is managed over the long term with ICS-containing treatment. If needed, day-to-day symptoms are also managed with pre-emptive reliever (SABA or ICS-formoterol) taken before exercise.

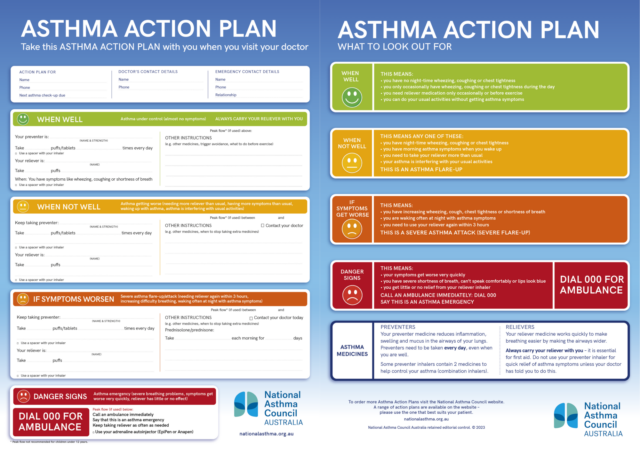

Explicit instructions on prevention and management of exercise-induced symptoms should be included in the patient’s written asthma action plan.

Patients with asthma who experience symptoms with physical activity should be reassured that exercise-induced symptoms can be managed effectively and should not be a reason to avoid exercise.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction can occur in people with no other characteristic features of asthma, mainly competing athletes. Specialist referral should be considered for athletes.

Athletes who meet the diagnostic criteria for asthma should be treated for asthma. Prescribers should check rules for asthma medicines permitted in sports.

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is defined as a transient narrowing of the lower airway after exercise.[Weiler 2016]

The most common symptoms of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction are wheeze, a feeling of chest tightness, dyspnoea, and cough.[Weiler 2016] Symptoms may also include excess production of mucus, and a subjective feeling of poor cardiopulmonary fitness despite good actual fitness. Children with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction may also report sore throat or chest pain.[Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction typically occurs after exercise, within 15 minutes of stopping high-intensity aerobic activity.[Grandinetti 2024] Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously within approximately 1 hour.[Grandinetti 2024]

The main cause of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is epithelial damage in the bronchial tree including the peripheral airways.[Greiwe 2020, Grandinette 2024] The exact mechanism is not fully known.[Greiwe 2020, Grandinette 2024]

Two hypotheses have been proposed:[Grandinetti 2024]

In athletes, epithelial dehydration caused by hyperventilation during aerobic exercise is thought to be the main mechanism for exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Grandinetti 2024] Air pollution (especially particulate matter with diameter <10 micrometres), low air temperature, and low air humidity have been shown to damage the airway epithelial barrier and promote bronchial inflammation and hyperresponsiveness.[Grandinetti 2024] In swimmers training in chlorinated pools, exposure to chloramines above the water may be associated with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Weiler 2016]

Common conditions that mimic asthma with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction include cardiopulmonary deconditioning and inducible laryngeal obstruction.[Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024] Exercise-induced dyspnoea due to poor fitness and hyperventilation is common in children, adolescents and obese patients. [Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024] Exercise-induced laryngeal dysfunction is characterised by inspiratory stridor. Exercise-induced hyperventilation should also be considered, especially in adolescents.[Towns 2009, Tilles 2010]

Differential diagnosis of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes includes other laryngeal conditions such as exercise-induced laryngeal prolapse, exercise-induced laryngomalacia.[Greiwe 2020] Other causes of exercise-induced dyspnoea include cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolus and pneumomediastinum.[Greiwe 2020]

Spirometry is required in the investigation of exercise-induced symptoms.[Weiler 2016] If lung function is normal both before and after bronchodilator in a patient with suspected exercise-induced bronchoconstriction without known asthma, bronchial provocation testing may be indicated with an appropriate challenge (e.g. exercise, mannitol or eucapnic voluntary hyperventilation).[Weiler 2016]

Cardiopulmonary fitness testing or flexible laryngoscopy may be required to identify alternative causes of symptoms.[Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is common among people with asthma.[Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024] Estimates of the prevalence of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children and adolescents with asthma range from 20% to 90%.[Grandinetti 2024]

Frequent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction suggests poor asthma control.[Weiler 2016]

ICS-containing treatment can decrease the frequency and severity of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children and adults.[Weiler 2016, Koh 2007]

After starting ICS treatment, it may take weeks (or even months) to achieve the full bronchoprotective effect.[Koh 2007, Hofstra 2000]

In one study, budesonide-formoterol taken as needed (approved for adults and adolescents) was as effective as regular maintenance low-dose ICS in preventing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Lazarinis 2014]

ICS treatment may not eliminate exercise-induced symptoms for every patient.[Weiler 2016]

Exercise-induced symptoms in adults, adolescents and children can be prevented by taking a reliever 15 minutes before exercise.[Weiler 2016, Grandinetti 2024] Options include salbutamol (e.g. two inhalations of 100 microg/actuation) or, in adults and adolescents, ICS-formoterol.[Grandinetti 2024]

Patients who use ICS-formoterol as their reliever can take it before exercise, instead of taking salbutamol.

Warming up 10–15 minutes before exercise induces a refractory period of approximately 2 hours without exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Grandinetti 2024] Exercise with high-intensity intervals, and exercise with a combination of low- and high-intensity intervals are both effective as warm-up for this purpose.[Grandinetti 2024]

Breathing through the nose during exercise, or wearing a face mask in cold weather, may reduce the risk of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.[Grandinetti 2024]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is more common among athletes who participate in sports that involve prolonged strenuous physical activity in cold and/or dry air (e.g. winter sports, soccer, long-distance running, basketball) or in swimmers, than among athletes in sports that require intermittent exertion.[Greiwe 2020] Rates are highest among athletes with atopy.[Greiwe 2020]

Estimated rates of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction among professional athletes range between 30% and 70%, depending on the type of sport.[Greiwe 2020]

Some athletes only experience exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in winter or in pollen season.[Weiler 2016]

Some competing athletes develop exercise-induced bronchoconstriction as an isolated symptom, without other typical asthma symptoms.[Greiwe 2020]

Competing athletes may be subject to World Anti-Doping Agency diagnostic documentation requirements for therapeutic use exemption for asthma medicines, including findings of detailed history and clinical examination, spirometry, and (if required) bronchial provocation.[WADA 2025]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes who meet diagnostic criteria for asthma should be managed as asthma, with ICS-containing treatment and a rapid-acting bronchodilator to manage symptoms.

Excessive use of SABA (particularly in athletes who practice frequent training) can result in tachyphylaxis and loss of the bronchoprotective effect during exercise.[Grandinetti 2024]

Specialist referral for investigation and management should be considered for athletes. Prescribers should check restrictions on medicines permitted in sports.

Sport Integrity Australia’s information on asthma medication in sport

World Anti-Doping Agency guidelines for physicians on therapeutic use exemption for asthma

Centre for Research Excellence in Treatable Traits’ toolkit on inducible laryngeal obstruction

Physical training is not a primary treatment for asthma, but should be recommended for adults and children with asthma as part of overall asthma management, for its beneficial effect on quality of life.[Carson 2013]

Supervised exercise training programs, particularly aerobic exercise, are effective in improving cardiorespiratory and functional fitness in adults with asthma.[Valkenborghs 2022]

Aerobic exercise training may also improve symptom control [Hansen 2020, McLoughlin 2022] and lung function [Hansen 2020] in adults with asthma.

Swimming training is well tolerated in adolescents with stable asthma, and improves lung function as well as cardiopulmonary fitness.[Beggs 2013] However, frequent exposure to chloramines in indoor pool air is associated with exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in competitive swimmers.[Weiler 2016]

Beggs S, Foong YC, Le HC, et al. Swimming training for asthma in children and adolescents aged 18 years and under. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4: CD009607.

Carson KV, Chandratilleke MG, Picot J, et al. Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 9: CD001116.

Grandinetti R, Mussi N, Rossi A, et al. Exercise-Induced bronchoconstriction in children: state of the art from diagnosis to treatment. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 4558.

Greiwe J, Cooke A, Nanda A, et al. Work Group Report: Perspectives in diagnosis and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in athletes [published correction appears in J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 605.] J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 2542-2555.

Hansen ESH, Pitzner-Fabricius A, Toennesen LL, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training on asthma in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 2000146.

Henriksen AH, Tveit KH, Holmen TL et al. A study of the association between exercise-induced wheeze and exercise versus methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2002; 13: 203-8.

Hofstra WB, Neijens HJ, Duiverman EJ. Dose-response over time to inhaled fluticasone propionate: treatment of exercise- and methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction in children with asthma Pediatr Pulmonol 2000; 29: 415-423.

Koh MS, Tee A, Lasserson TJ. Inhaled corticosteroids compared to placebo for prevention of exercise induced bronchoconstriction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; CD002739.

Lazarinis N, Jørgensen L, Ekström T, et al. Combination of budesonide/formoterol on demand improves asthma control by reducing exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Thorax 2014; 69: 130–136.

McLoughlin RF, Clark VL, Urroz PD, et al. Increasing physical activity in severe asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2022; 60: 2200546.

Tilles SA. Exercise-induced respiratory symptoms: an epidemic among adolescents. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010; 104: 361-367.

Towns SJ, van Asperen PP. Diagnosis and management of asthma in adolescents. Clin Respir J 2009; 3: 69-76.

Valkenborghs SR, Anderson SL, Scott HA, Callister R. Exercise training programs improve cardiorespiratory and functional fitness in adults with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2022; 42: 423-433.

WADA. TUE Physician Guidelines – Asthma – Version 9.2 – January 2025. World Anti-Doping Agency 2025.

Weiler JM, Brannan JD, Randolph CC, et al. Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction update–2016. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138:1292-1295.e36.

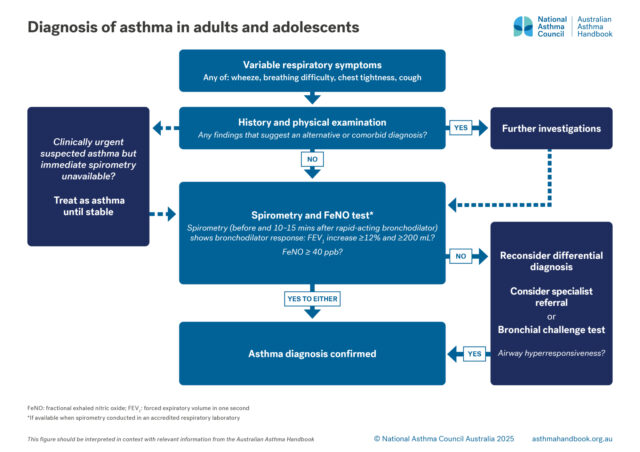

Adults and Adolescents

Investigation of suspected asthma and diagnostic criteria in adolescents and adolescents.

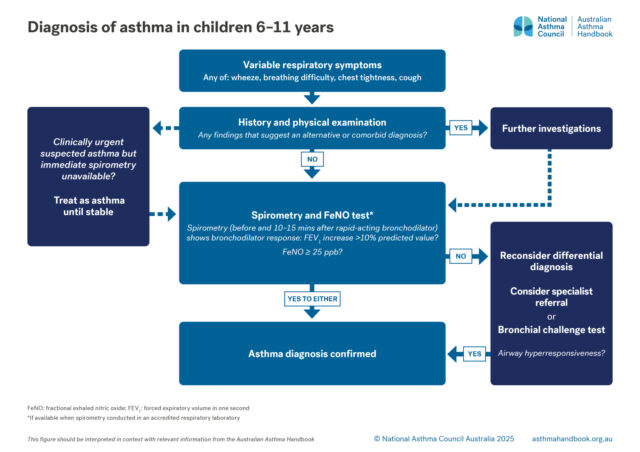

Children 6-11 years

Investigation of suspected asthma and diagnostic criteria in children 6–11.

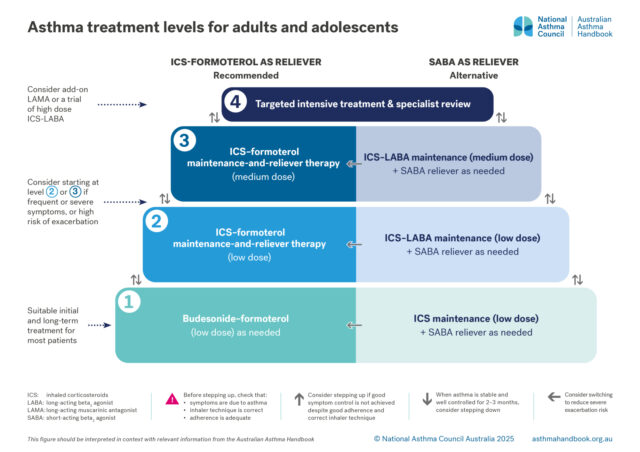

Principles of management

Goals and principles of asthma management in adults and adolescents.

Medication management

Recommended and alternative treatment options for patients 12 years and over, according to intensity of treatment…

Principles of management

Goals and principles of asthma management in primary school-aged children.